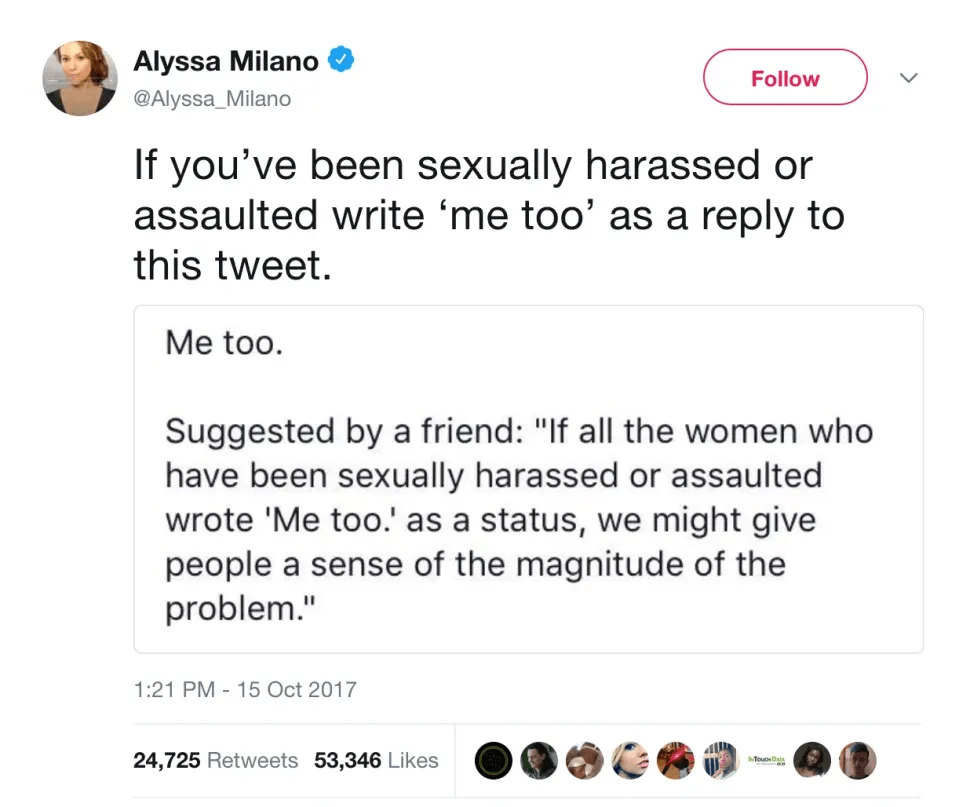

It all began with a tweet from actress Alyssa Milano. The tweet featured an image captioned, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.” The image itself read: “Me too. Suggested by a friend: ‘If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.’” Posted on October 15, 2017, that tweet ignited one of the fastest-spreading social movements of our time. Within just 24 hours, the phrase had taken over social media, generating millions of posts and shares. Thus began the #MeToo movement.

It’s important to note, however, that while Milano’s tweet brought the movement into the mainstream, the phrase “Me Too” had been used long before by activist Tarana Burke. Burke coined the term back in 2006 on MySpace to raise awareness about the widespread issue of sexual violence, particularly against Black women and girls. Her goal was to foster a sense of solidarity among survivors and to let them know they weren’t alone. Although her work gained traction within certain communities, it wasn’t until the Harvey Weinstein scandal in October 2017 that #MeToo exploded on a global scale. As horrifying accounts of Weinstein’s abuse came to light, women around the world felt empowered to share their own stories and name their abusers. Neither Burke nor Milano anticipated just how massive the movement would become—celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow and Jennifer Lawrence even joined in. Before #MeToo, society often defaulted to doubting or silencing women who spoke out. This movement flipped that norm. I’ll explore the specific impacts of the movement later in this paper, but I want to emphasize that while the original focus was on men abusing women, the movement has since expanded to include same-sex assault and abuse against men as well.

According to Bowers, Ochs, Jensen, and Schulz in the third edition of The Rhetoric of Agitation and Control, there are three key conditions that define a social movement—and the #MeToo movement meets all of them. First, the movement must be “organized by people outside the normal decision-making establishment.” Tarana Burke fits this exactly. Born and raised in the Bronx, she came from a low-income background and was sexually assaulted multiple times as a child and teen. These traumatic experiences shaped her path toward activism. In her early years, she created a nonprofit called “Just Be” to empower Black girls aged 12 to 18 and used “Me Too” as a way to connect survivors and reduce shame. While she’s been a strong, influential figure for years, Burke was never part of the establishment—if she were, she wouldn’t have had to fight so hard for women in the first place.

As for Alyssa Milano, she came from a different background—born into a wealthy Brooklyn family, she gained fame through acting roles on shows like Who’s the Boss? and My Name is Earl. Yet despite her celebrity status, Milano wasn’t part of the legal or political systems that deal with sexual abuse cases. Over the years, she’s used her platform to support causes ranging from AIDS awareness to clean water initiatives. When she saw the Weinstein story and reflected on her own experiences, she tweeted that now-famous message, hoping to offer women a way to speak out without reliving their trauma in detail.

The second requirement of a social movement is that it must advocate for significant social change. #MeToo did just that. Before the movement, people often ignored or denied how common sexual harassment and abuse really were. Burke and Milano helped change that. The movement raised public awareness and demanded justice—leading to the resignation or firing of many powerful men across industries. One shocking example was NBC’s Matt Lauer, a figure many Americans, myself included, watched daily. Learning that someone I admired had used his influence to harm women truly opened my eyes to how prevalent and insidious this issue is.

Finally, the third condition is that a movement must “encounter significant resistance from the establishment.” #MeToo has faced plenty. Many accused women of lying or exaggerating. Others debated the definition of sexual abuse or became defensive, with some men now avoiding women in the workplace out of fear rather than understanding. Still, the movement persisted. As of July 24, 2020, #MeToo remains strong. Its staying power proves it’s more than just a trend—it’s a cultural shift. Women live with less fear now, knowing that they are not alone and that they will be supported.

There’s no question that #MeToo has left a lasting mark. Our textbook outlines eight major lessons from the movement, but the one that resonates most with me is number seven: “This movement has effectively addressed the myth that the legal system provides an effective way to address sexual harassment” (425).

Understanding how difficult it is to bring a case to court is crucial. While sexual assault laws may appear straightforward, proving them often isn’t. Survivors may fear retaliation or feel overwhelmed by the legal process. #MeToo spotlighted this issue and encouraged survivors to speak up despite those fears. The strength in numbers gave many the courage to demand justice—not just for society, but for themselves.

Of course, there are still critics of the movement. Some argue that it has been misused or blown out of proportion. Conservative commentator Tomi Lahren tweeted on July 20, 2020: “Both the #MeToo and BLM movements have been hijacked by opportunists looking for relevance, a payout or both. Sad.” Personally, I find her tweet nonsensical, but it reflects a larger discomfort people have with acknowledging just how widespread abuse really is. Most of the opposition I’ve seen comes from either misunderstanding or flat-out denial. It’s easier for some people to believe that these things don’t happen than to confront the painful truth that they do—and often.